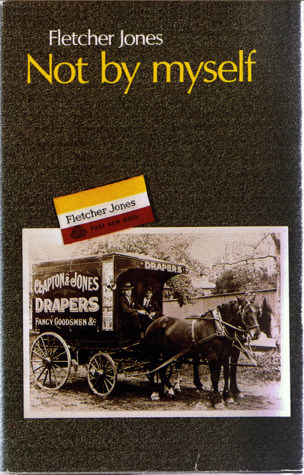

Not by myself by Fletcher Jones

2013年の春、神戸の賀川記念館にオーストラリアで大手衣料品業を打ち立てた故フレッチャー・ジョーンズ氏の長男からジョーンズ氏の著作「Not by myself」が届いた。ジョーンズ氏の成功物語はすでにドキュメンタリーとしてオーストラリアで放映され、その中で賀川豊彦に対する思いが語られている。「not by myself」の中では賀川豊彦と題して一つの章が設けられている。その英文を紹介したい。

57. Toyohiko Kagawa

The eminent American journalist Basil Matthews first told me about Toyohiko Kagawa in the early 1930s’ He described him as one of the seven greatest men in the world then.

This inspired me to read everything Kagawa had written which was available in English. Great was my excitement to learn that Kagawa was coming to Australia. I made up my mind he should come to Warrnambool.

Conditions during the great depression of 1929-1931 certainly made me stop and think and wonder. I wanted to know why the rich were getting richer and the poor poorer.

Distribution of the world’s wealth was and still is the world’s most pressing problem. What could 1 do about it?

I tried to read the writings of the world’s great economists and social reformers. Much of the phraseology was beyond my capabilities, but 1 ploughed through works of Victor Gollancz and Professor Harold Laski; through J B S Haldane and the Webbs, then I studied the concept of the cooperatives.

It was fascinated by the pioneer co-operative movement among the flannel weavers of Rochdale in England. They began by contributing three farthings a day until they could buy their own little flour gristing mill. Thus they made their own bread. Next they began to make their own boots assisted by the shoemakers of Scandinavia.

But finally the writings of Kagawa seemed most satisfying to me. I dreamed of going to Japan to study his production and consumer co-operatives. In 1936 I did go. Meanwhile in 1934 the great news of Kagawa’s Australian visit captivated us.

The name of Toyohiko Kagawa will not be a familiar one today but his life and work had a tremendous impact on Christian life and witness in Japanese industry. His work created a lot of interest in churches in the western world.

Kagawa was born in 1888. He died in 1960. He was the son of a wealthy Samurai and a geisha. They both died when he was a mere toddler. He was brought up by his stepmother

and then, after her death, by an uncle.

When he was a student he became a Christian. His uncle threw him out of the house. He had been brought up in the Buddhist faith and schooled in the thoughts of Confucius.

Now he was rejecting both of these stalwarts of the past.

He had been taught English by two American missionaries, Dr Logan and Dr Myer. They in their Christian faith gave him answers to some of the doubts he had about his own faith. Jesus said, ‘Consider the lilies of the field’.

Buddhism said material things, even lilies were nothing. Kagawa was converted by the Missionaries’s teaching and by the example of their compassion. They even sponsored his university education.

He had tremendous feeling for the poor and the sick. He felt deeply that the Church and the individual Christian should practise what they preached. He lived in a two-room

apartment house in the slums of Tokyo for thirteen and a half years. He filled it with the homeless. He lived as a son to one known as ‘Old woman of the cats’. He adopted a child who lived with its family in overcrowded conditions.

He rescued a boy from a mother in prison. He tutored a working boy at five in the morning. He received the sick at 7 a.m. He was persecuted because he preached the gospel

from street corners. He studied the slums and the plight of the unemployed in America. He visited Gandhi in India and he studied the co-operative movements among the dairies and fisheries of Denmark.

To Japan he brought tremendous social reforms. He established a trail of schools, kindergartens and nurseries in churches throughout the country, in his belief that the

church should be compelled to practise what it preached.

He helped the growth of the Japanese co-operative movement. He was involved in consumers’ co-operatives, university students’ credit unions and farmers’ co-operatives,

even credit co-operative pawn shops. His book, Brotherhood Economics, published in 1937, advocated brotherly love between producers and consumers. He did not like the materialism involved in capitalism and in communism.

It was this great man I wanted to bring to Warrnambool. The secretary of the group organising his itinerary was in Brisbane. I wrote him a letter. I received a very nice letter in reply regretting that Warrnambool could not be fitted into the programme. I wrote another by return mail and then another and another. I collected some money from friends and sent a cheque to cover expenses. At long long last the battle was won. The committee was persuaded to yield to what they called my ‘extraordinary enthusiasm’.

We formed a little committee in Warrnambool consisting mainly of Toe H men. On 8(h May, 1935 Kagawa came.

During his stay in Warrnambool we had sessions at 3 p.m., 7.30 p.m. and 9 p.m. The town hall was packed each time. Excitement was high.

Kagawa had a high, rather squeaky voice. There was no amplification. To reflect his voice from the stage down to the back of the hall we joined three trestle tables together

and had them pitched over his head, sloping from the floor of the stage upwards and outwards. This sloping canopy carried his voice most effectively.

As we looked at this frail little man – he was only about five feet tall-up there under the canopy we marvelled at his open-handedness and human compassion. Many of us

were glad that we had already learned his poem ‘Penniless’.

Penniless awhile

Without food I can live

But it now breaks my heart

To know I cannot give.

Penniless I can share my rags

But 1 cannot bear to hear

Starved children cry.

Kagawa and his secretary, Mr Ogawa, stayed at our home in Jamieson Street. I could write many pages on what happened to us during this memorable visit. Kagawa and Ogawa were both learned geologists. They were up at day-break wandering around Warrnambool, picking up and examining stones.

Four of the committee travelled back to Melbourne with Kagawa. The trip was most exciting. There were queues of people lining the road at each township. We made eleven

stops. Kagawa gave eight addresses.

The committee that brought him to Australia had arranged for him to have a suite at the top of the Victoria Palace. A voluntary staff met visitors at the door of the Victoria and escorted them up aloft. I had several memorable sessions with Kagawa alone, I knew that I was in the presence of a saint:

I had no doubt that Basil Matthews was right.

Kagawa had a global mind. For instance, he was fascinated by the many types of honeyeaters in the bush around Warrnambool. (The number was 140.) He enquired about

Adam Lindsay Gordon’s home ‘Dingley Dell’ which was across the South Australian border. He even knew and recited two of Gordon’s poems.

Early in the trip he showed great interest in Toe H. He knew that we had a particularly live branch at Warrnambool and it was evident that he had read all that he could about Tubby Clayton and the movement. This gave us a bond in common.

Certainly it was very challenging indeed to meet and to hear this great man who had thrown himself deliberately into the slums to meet the people, the people, the people.

Before Kagawa came to Warrnambool in 1935 I wrote Seven thumbnail sketches of Dr Toyohiko Kagawa, the St Francis of the Japanese Slums. They were printed in the Warrnambool Standard as a series over the couple of weeks before his visit to Warrnambool. They are reproduced in an Appendix to illustrate the things that impressed me about this great man.

With great excitement and gratitude I went to Japan the very nexl year to meet Kagawa again and to see for myself something of what he had actually done.

Understanding wife that she was. Rena could see it sticking out a mile lhat I must go.

It was indeed a great sacrifice for a young wife with three young children, and I knew it.

June 1936 consequently saw me on the Kama Maru landing in that then weird land, doing my humble best to visualise the possibilities of using the best of what was to be seen back in Australia.

It seemed that in Japan, well-run co-operatives could handle almost any activity. For example, they even had Christian co-operative pawn-shops to alleviate the distress

of the countless thousands of small shopkeepers, who were forced to pawn last season’s left-over merchandise in order to buy in for the coming season.

The regular pawn-shops charged these poor beggars an alarming 35% compound interest. Kagawa’s co-operative pawnshops were supported by overseas friends, mainly churches, and were charging a mere 1%.

Kagawa provided me with a new student guide each day to guide my study time from town to town. It was cheaper to travel with an experienced native than to travel alone. Five months of this in the field was perhaps as good as a university course.

Going off the beaten track with the Japanese in those days was jam-packed with difficulties. I travelled third class mainly because there wasn’t any fourth class. I ate and slept Japanese style. The food was raw fish, seaweed, eggplant and other raw materials which took some swallowing, but it made me a good strong boy.

After returning to Australia, the idea of turning my own business into a staff co-operative grew within me. I shared my thoughts with Rcna. She encouraged me, but we waited a while. Then Neil Symons, Master of Laws and our solicitor, framed our scheme with all its Segal and business perplexities. He has outlined the scheme in an appendix to the book. Neil Symons is now the General Managing Director of F J & Staff.

Not by myself

by Sir Fletcher Jones

Pub. by Kingfishse Books PTY Ltd

First Published 1977